“The same prudence, which, in private life, would forbid our paying our money for unexplained projects, forbids it in the disposition of public moneys.” - Thomas Jefferson

Why is the 2009 Environmental Assessment for the OFF-ROAD trail in Segment 9 identical to the 2008 Environmental Assessment for an ON-ROAD trail in Segment 9?

Why is the 2009 cost projection for the OFF-ROAD trail identical to the 2008 cost projection for an ON-ROAD trail in Segment 9?

Fifteen years later, it’s time for an accurate Environmental Assessment

The National Park Service publicly states that in 2009 NPS determined the entire Sleeping Bear Heritage Trail has “no significant impact” and suggests that automatically applies to Segment 9. It’s been fifteen years since Segment 9 of the Heritage Trail was proposed in 2009 and the Environmental Assessment was presented to the public. There is so much more information now available to the public, especially now that the route is actually staked for people to understand. After completing independent professional reports, Borealis Consulting LLC and Mansfield & Associates have both independently recommended an accurate Environmental Assessment (EA) / Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) be completed for Segment 9.

As expounded below, the NPS 2009 Trailway Plan and Environmental Assessment:

did not identify the rich conifer wetlands along west Traverse Lake Road (TLR) or the need to build boardwalks,

did not reference the need for a bridge crossing across Shalda Creek,

did not mention the wooded dune forest along TLR and the need for extensive tree clearing,

did not recognize the State protected Critical Dune Area which exists for 85% of trail length,

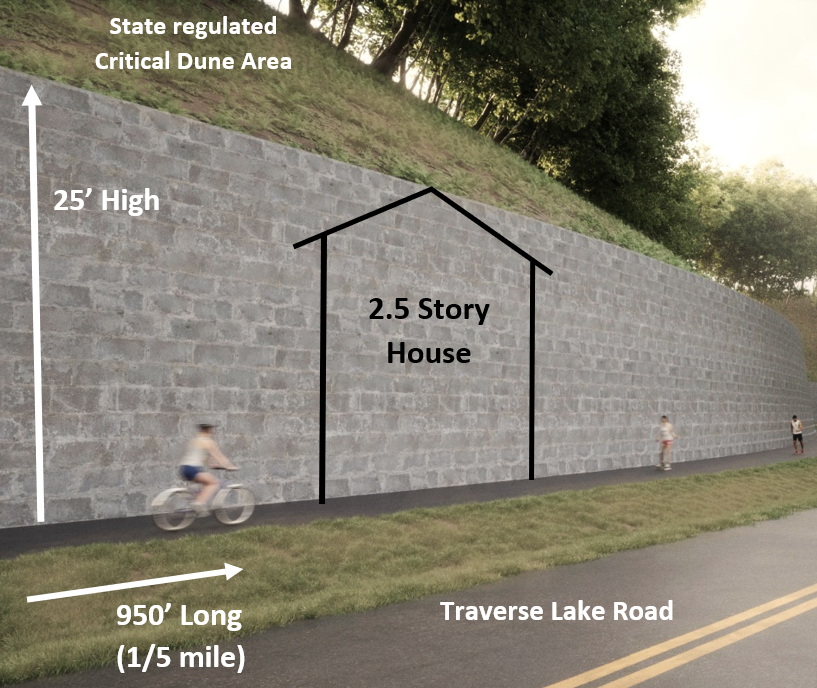

did not reference the steep critical dunes along TLR and the need to build large retaining walls,

did not reference the trail going through globally rare and State concern wooded dune and swale complexes, and

did not reference the 2008 Lakeshore’s General Management Plan which prioritized areas for recreation and protection of the natural environment.

The flaws with the NPS 2009 Environmental Assessment for a proposed off-road trail along Traverse Lake Road become even more obvious when comparing the NPS 2008 Environmental Assessment for a proposed on-road trail along Traverse Lake Road. They are IDENTICAL. How can the Environmental Assessment for an OFF-road trail be the same as for an ON-road trail? Read more below.

The National Parks Conservation Association requests NPS to conduct a new EA considering alternatives

Since 1919, the National Parks Conservation Association (NPCA) has been the leading voice of the American people in protecting and enhancing the National Park System. NPCA and their 1.6 million members and supporters, including over 55,000 in Michigan, advocate for America’s national parks and work to protect and preserve the nation’s most iconic and inspirational places for present and future generations.

In their April 2024 letter to Lakeshore Superintendent Scott Tucker, NPCA writes: “Under the current alternative, the trail will need to be constructed in the State of Michigan’s regulated critical dunes requiring a 15 ft. retaining wall, extensive boardwalks through wetlands, reduction of canopy cover and habitat through the removal of 7,300 trees some culturally significant to the Odawa. A trail within this area would exacerbate impacts to forest diversity and water quality. NPCA requests the exploration of new alternatives with reduced environmental impacts to our beloved trail and associated resources.”

Cleveland Township opposes Segment 9

The Cleveland Township Board of Leelanau County, at their regular meeting held September 10, 2024, has formally rescinded their Sept 10, 2019 resolution that supported Segment 9. The change in position was a decision based on several factors including the significant construction cost of $15.5 million for 4.25 miles (something Supervisor Tim Stein called "fiscally irresponsible"), environmental concerns regarding dunes and wetlands, tree loss, and better alternative options. As part of their formal resolution, which passed unanimously 5-0, the Township Board stands in opposition to the construction of Segment 9. The Township's resolution of support for a trail extension down CR 669 to Bohemian Beach on Good Harbor Bay still stands. (News Story here)

Sleeping Bear Naturally requests NPS to conduct new EA and EIS for Segment 9

Sleeping Bear Naturally, on behalf of over 1,000 followers, sent a letter to NPS in April 2024 requesting a new Environmental Assessment (EA) for Segment 9 as well as a thorough and documented Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). The letter documents the various challenges and shortcomings of the 2009 NPS EA. As required by NEPA, an EA and EIS should be based on scientific information, thoroughly identify and evaluate impacts to the environment, and consider all alternatives that would mitigate the impacts, including alternative route options. A copy of the April 2024 letter can be found here. Sleeping Bear Naturally sent a follow-up letter to the NPS in September 2024 (which can be found here) along with a letter signed by 1600 individuals as of August 1, 2024 (which can be found here).

Sleeping Bear Naturally filed a request under the Freedom of Information Act for all communication, studies, engineering analysis and in comparison evaluation of alternatives related to Segment 9 between the shared on-road trail proposed in October 2008 and the separated off-road trail proposed in March 2009, only four winter months later with snow on the ground. A copy of the November 2024 FOIA request can be found here. In response to the FOIA request, the Office of the Secretary for the Department of Interior has indicated that no such records can be found (see letter here). An appeal was filed with the National Archives which also indicated that no such records can be found (see letter here). Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore also did not provide any documentation of assessment studies done between October 2008 and March 2009. The discovery process that was part of the court proceeding during the legal complaint filed by Little Traverse Lake Association also yielded no documentation that Segment 9 was ever revisited between the 2008 EA for an on-road trail and the 2009 EA for the proposed off-road trail (Fraser Trebilcock attorneys).

Northern Michigan Environmental Action Council requests a new EA

The Northern Michigan Environmental Action Council has worked to protect Michigan’s environment for over 43 years. In its letter to the National Park Service, NMEAC states: “Unnecessary environmental impacts of Segment 9 cannot be justified when feasible alternatives are overlooked … A new Environmental Assessment is urgently needed today in the face of new information.” A copy of the letter can be found here.

More information is available today than fifteen years ago

With more information publicly available now, the attractive sound bite statements of NPS and TART Trails, insisting there is no significant impact with the planned Segment 9 route, seem more and more unbelievable. Here is what is available today that was not available in 2009:

An independent botanical survey has now been completed based on actual staking of the proposed route.

An engineering analysis is now publicly available on the potential design and impacts through State-protected Critical Dune Area. MDOT should be informing the public of the proposed trail designs, which have not been publicly available or known.

Costs are being updated to reflect actual design requirements that were previously omitted.

There is greater understanding of the feasibility of alternatives in the Good Harbor area, alternatives with fewer known environmental impacts that still create diverse recreational opportunities complementing the existing 22 miles of the Heritage Trail.

There is a better understanding of user demand than was projected fifteen years ago.

Protecting the environment into the future is becoming increasingly important as climate change becomes more real today.

There is more public understanding of the errors and omissions contained in the NPS 2009 Environmental Assessment (EA), questioning why the EA for the 2008 proposed on-road trail along Traverse Lake Road (TLR) is identical to the EA for the 2009 proposed off-road trail along TLR.

Segment 9 has unique environmental features and engineering requirements that are not representative of the other 22 miles of existing Heritage Trail. It cannot just be lumped together and assuming the “no significant impacts” of other trail segments applies to Segment 9.

The National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA) requires the EA/EIS be revisited if there are significant new circumstances or information relevant to the environmental concerns that have bearing on the proposed action or its impacts. Certainly that is the case now. Environmental assessments are not timeless when times change. Wetland delineation reports are typically only valid for 5 years, only 3 if performed by EGLE, due to nature’s constantly changing conditions.

An Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) should be done for Segment 9 because an EIS was NEVER done. A new EA should be done for Segment 9 because of the errors and omissions in the 2009 EA. NPS has simply said an EA was done and the impact is not significant. But is that finding based on complete information that was detailed and accurate, or a subjective determination? To answer that question, one needs to spend time understanding the requirements of NEPA, what is involved in completing an EA and EIS, and what was included in the NPS 2009 EA. That detailed information is presented below for greater public understanding and consideration of various aspects related to trail planning, NEPA and Environmental Assessments.

Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians Opposes Segment 9

The Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians has formally expressed to NPS its opposition of the proposed Segment 9 Heritage Trail (copy of letter here). Thanks to their leadership and vision in stewarding our public lands for future generations.

“The proposed [Segment 9] extension threatens to disrupt delicate wetland ecosystems, which are vital to the environmental health of the region. Wetlands serve as critical habitats for a wide variety of species, including those that are culturally significant to the GTB. The proposed tree removal further exacerbates these environmental concerns, potentially leading to the destruction and a loss of biodiversity. Substantial tree removal will also limit the carbon capture ability of the present tree diversity thereby contributing to greenhouse gas emissions, an increasing environmental threat of global warming that may not have been completely considered in the initial stages of the review process.”

“Moreover, the proposed [Segment 9] extension encroaches upon areas protected under treaty rights that guarantee our Tribal members the ability to gather resources for subsistence and cultural practices. These rights are foundational to our way of life and are legally protected. Any infringement upon these rights is not only a violation of our treaties but also a direct threat to the cultural heritage and sustenance of our community.”

White House Executive Order 13145 requires agencies to consult with Tribes on Federal Policies and Projects

Executive Order 13145 of November 6, 2000 (Consultation and Coordination With Indian Tribal Governments), charges all executive departments and agencies with engaging in regular, meaningful, and robust consultation with Tribal officials in the development of Federal policies that have Tribal implications. Tribal consultation under this order strengthens the Nation-to-Nation relationship between the United States and Tribal Nations. The Presidential Memorandum of November 5, 2009 (Tribal Consultation), requires each agency to prepare and periodically update a detailed plan of action to implement the policies and directives of Executive Order 13175. This memorandum reaffirms the policy announced in that memorandum.

Tribal representation was not included in the initial efforts to develop the Heritage Trail concept leading up to the proposed Segment 9 in the 2009 Trailway Plan and Environmental Assessment. Tribal representation was not part of the 2018/2019 Segment 9 Heritage Trail Workgroup. They have not been consulted in the initial designs being contemplated. Why has the executive directives not been followed?

Federal Lands to be Co-Stewarded by Tribal Nations

The Secretary of Interior issued specific directive Secretary’s Order 3403 on "CO-STEWARDSHIP" of federal lands given to National Parks in working with Tribes. The tribes are to have a significant role in how federal lands are to be stewarded and utilized. The Executive Order is to

“Ensure that all decisions by the Departments relating to Federal stewardship of Federal lands, waters, and wildlife under their jurisdiction include consideration of how to safeguard the interests of any Indian Tribes such decisions may affect; and to Make agreements with Indian Tribes to collaborate in the co-stewardship of Federal lands and waters under the Departments’ jurisdiction, including for wildlife and its habitat.”

National Park Service under directive to implement Co-Stewardship of lands with Tribal Nations

Policy Memorandum 22–03, United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, was sent to the National Leadership Council Superintendents (National Park Service, 2023). That memorandum, sent by the NPS Director, is about fulfilling the NPS Trust Responsibility to Indian Tribes, Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians in the Stewardship of Federal Lands and Waters. The term co-stewardship is used throughout to describe a new government-to-government relationship between US tribes and the NPS.

“To increase opportunities for Indian and Alaska Native Tribes and Native Hawaiians to fully participate in Federal decision making and to safeguard their interests, the NPS will strive to engage in co-stewardship where: 1. Federal lands or waters, including wildlife and its habitat, are located within or adjacent to an Indian or Alaska Native Tribe’s lands; or 2. an Indian or Alaska Native Tribe has subsistence or other rights, including treaty-reserved rights, or interests in Federal lands or waters even when that Indian or Alaska Native Tribe’s lands are not adjacent to those Federal lands or waters.”

Tribes are more than stakeholder groups - they are sovereign governmental entities

State of Michigan Executive Directive 2019-17 is a policy directive in working with Tribes and their input into agency decisions. Tribal nations are not just a "stakeholder group;” they are a sovereign nation with recognized governmental authority and can determine when inappropriate policy direction is being taken by state or federal agencies that impacts their rights, lands and governance.

“Each department and agency must recognize, and must ensure its policies and practices effectuate, the following fundamental principles concerning Indian tribes, bands, and communities that the Secretary of the United States Department of Interior has recognized as Indian tribes pursuant to the Federally Recognized Indian Tribe List Act of 1994, 25 USC 4 79a: (a) Federally recognized Indian tribes are sovereign governmental entities. (b) Federally recognized Indian tribes possess inherent authority to exercise jurisdiction over their respective lands and citizens. (c) Federally recognized Indian tribes possess the right to self-governance and self determination. (d) The United States has a unique trust relationship with federally recognized Indian tribes as set forth in the United States Constitution, treaties, statutes, executive orders, court decisions, and the general course of dealings of the United States with the Indian nations. (e) The State of Michigan has a unique government-to-government relationship with each of Michigan's federally recognized Indian tribes, and that relationship is shaped by accords, compacts, statutes, court opinions, and a multitude of intergovernmental interactions.”

Treaty Rights of 1836

Segment 9 is part of federal lands that are covered under the Treaty Rights of 1836, which includes hunting and gathering rights. Information on tribal hunting and fishing can be found here and a map of the treaty lands can be found here.

NPS Master Plan, Wilderness Area bending to Segment 9 route?

2008 General Management Plan

In 2008, after much study and input over several years, the National Park Service adopted a General Management Plan that is to guide future utilization of Sleeping Bear National Lakeshore. That effort also included the identification of a proposed wilderness area.

The preferred alternative for the General Management Plan included much of the Good Harbor area to be included and managed as a wilderness area. Note that the area north of Traverse Lake Road to Bufka Farm and east to M-22 (circled) was included in that proposed wilderness area due to its environmental significance and was proposed in early versions of the introduced wilderness area legislation.

According to the General Management Plan, NPS identified in 2008 the area along Traverse Lake Road to be for experiencing nature while the area along Bohemian Road / CR 669 and Lake Michigan Road was designated for recreational purposes. The area between Lake Michigan Road and Lake Michigan was also carved out of the wilderness area with a 600’ recreational zone along the beach. Cleveland Township also identifies in their Master Plan the area along Lake Michigan Road as a area for additional recreational use and development.

After identifying important environmental management goals, NPS determined in 2008 that the features and ecosystems along Traverse Lake Road and the Bufka Farm area was more suited to be managed as a wilderness area rather than for recreational use.

2009 Segment 9 Heritage Trailway Plan

In 2009, NPS published the Leelanau Scenic Heritage Route Trailway Plan and Environmental Assessment with the proposed Segment 9 routed along Traverse Lake Road and north to Bufka Farm through an area that was designated to be managed as wilderness. The trail route also did not utilize the corridors in the Good Harbor area that were identified as recreational opportunities within the General Management Plan. Why was that proposed Segment 9 route drawn on the map through the proposed wilderness area when NPS had identified other areas in Good Harbor Bay to be a priority for recreational use?

2014 Wilderness Area legislation signed into law

In 2014, the Wilderness Area legislation was passed after being introduced for many years. The Wilderness Area boundary begins 100’ from the centerline of any county road (e.g. Bohemian Road / CR 669) and 300 feet from the centerline of any state highway (e.g. M-22). The Wilderness Area now excludes the vulnerable dune and swale complex and rich conifer swamp between TLR and Bufka Farm (see circle area), which was identified in the preferred alternative in the General Management Plan to be part of the proposed Wilderness Area. The revision in the Wilderness Area and the new eastern boundary conveniently followed the exact line on the map for the proposed Segment 9 Heritage Trail route. The Segment 9 trail route should have been drawn around the proposed Wilderness Area rather than the boundary of the Wilderness Area being drawn around the proposed Segment 9 trail route.

Why did the proposed Segment 9 route take precedence over the General Management Plan that, after much study and effort, identified these to be a wilderness area as the preferred alternative? The General Management Plan is supposed to be a guiding document for management of unique areas within the Lakeshore. The proposed Segment 9 route is not consistent with the 2008 General Management Plan. It appears that a trail route was drawn as a line on the map without looking at the proposed wilderness area, the General Management Plan or without understanding or identifying the environmental features that actually existed in this area. The line was drawn on a map and nothing else has mattered ever since. Fortunately, that line doesn’t have to be permanent in the human environment. The right approach can still be used.

A completed Wilderness Management Plan (WMP) was supposed to be completed by 2019,within five years of wilderness designation. NPS Superintendent Scott Tucker has explained per our inquiry via email (April 2024) about a copy of the WMP: “The park has not completed a Wilderness Manage Plan at this time. Funding and capacity are always components that delay a project. In this case, funding has not been secured for the plan. For Sleeping Bear Wilderness, some wilderness planning has occurred…. This process is consistent with Keeping it Wild 2 An updated interagency strategy to monitor trends in wilderness character across the National Wilderness Preservation System. We continue to peruse the Management Plan as funding and time allow.”

It is interesting there is no budget priority or time to develop a Wilderness Management Plan but time can be spent on trail planning along with spending millions to build an adjacent trail through similar nearby extension of wilderness areas. The 2008 NPS General Management Plan identified the Bufka Area as a proposed Wilderness Area and has globally rare and State Concern ecosystems. NPS states the trail does not cross the boundary line of 2014 Wilderness Area but it runs right along side. This area should be managed in spirit and in practicality as a wilderness area due to the vulnerable ecosystems and sensitive environmental features. The “Keeping it Wild 2” policy document, that Superintendent Tucker referred to, references five qualities of a Wilderness Area (pages 10-12):

UNTRAMMELED The Wilderness Act states that wilderness is “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man,” that “generally appears to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature” and “retain[s] its primeval character and influence.” This means that wilderness is essentially unhindered and free from the USDA Forest Service RMRS-GTR-340. 2015. 11 intentional actions of modern human control or manipulation. This quality directly relates to “biophysical environments primarily free from modern human manipulation and impact” and “symbolic meanings of humility, restraint, and interdependence that inspire human connection with nature” described in the above definition of wilderness character.

NATURAL The Wilderness Act states that wilderness is “protected and managed so as to preserve its natural conditions.” This means that wilderness ecological systems are substantially free from the effects of modern civilization. Within a wilderness, for example, indigenous plant and animal species predominate, or the fire regime is within what is considered its natural return interval, distribution over the landscape, and patterns of burn severity. This quality directly relates to “biophysical environments primarily free from modern human manipulation and impact” described in the above definition of wilderness character. The Natural Quality is preserved when there are only indigenous species and natural ecological conditions and processes, and may be improved by controlling or removing non-indigenous species or by restoring ecological conditions.

UNDEVELOPED The Wilderness Act states that wilderness is “an area of undeveloped Federal land … without permanent improvements or human habitation,” “where man himself is a visitor who does not remain” and “with the imprint of man’s work substantially unnoticeable.” This means that wilderness is essentially without permanent improvements or the sights and sounds of modern human occupation. This quality is affected by “prohibited” or “nonconforming” uses (Section 4(c) of the Wilderness Act,), which include the presence of modern structures, installations, and habitations, and the administrative and emergency use of motor vehicles, motorized equipment, or mechanical transport. Some of these uses are allowed by special provisions required by legislation. This quality directly relates to “personal experiences in natural environments relatively free from the encumbrances and signs of modern society” and “symbolic meanings of humility, restraint, and interdependence that inspire human connection with nature” described in the above definition of wilderness character.

SOLITUDE OR PRIMITIVE AND UNCONFINED RECREATION The Wilderness Act states that wilderness has “outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation.” This means that wilderness provides outstanding opportunities for recreation in an environment that is relatively free from the encumbrances of modern society, and for the experience of the benefits 12 USDA Forest Service RMRS-GTR-340. 2015. and inspiration derived from self-reliance, self-discovery, physical and mental challenge, and freedom from societal obligations. This quality focuses on the tangible aspects of the setting that affect the opportunity for people to directly experience wilderness. It directly relates to “personal experiences in natural environments relatively free from the encumbrances and signs of modern society” described in the above definition of wilderness character.The Solitude or Primitive and Unconfined Recreation Quality is preserved or improved by management actions that reduce visitor encounters, reduce signs of modern civilization inside wilderness, and remove agency-provided recreation facilities.

OTHER FEATURES OF VALUE The Wilderness Act states that wilderness “may also contain ecological, geological, or other features of scientific, educational, scenic, or historical value.” This quality captures important elements or “features” of a particular wilderness that are not covered by the other four qualities. Typically these occur in a specific location, such as archaeological, historical, or paleontological features; some, however, may occur over a broad area such as an extensive geological or paleontological area, or a cultural landscape. The Other Features of Value Quality directly relates to “personal experiences in natural environments relatively free from the encumbrances and signs of modern society” and “symbolic meanings of humility, restraint, and interdependence that inspire human connection with nature” described in the above definition of wilderness character.

Premises for Using These Five Qualities Metaphorically, wilderness character is like a violin or another musical instrument composed of separate pieces that interact to form something greater than the sum of its parts: music and ultimately the feelings this music evokes. Similarly, these five qualities together form the physical, social, and managerial setting of a wilderness, in turn providing scientific, cultural, educational, and economic values to society (Cordell and others 2005). In addition, spiritual (Moore 2007, Nagle 2005), ethical (Cafaro 2001), psychological (Schroeder 2007), democratic (Turner 2012), and other intangible societal and individual values and benefits are derived from this wilderness setting (Havlick 2006). In total, these five qualities create a unique setting, which provides what the Wilderness Act describes as the “benefits of an enduring resource of wilderness.”

Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore was established by Act of Congress October 21, 1970. Public Law 91-479 states,

"…the Congress finds that certain outstanding natural features, including forests, beaches, dune formations, and ancient glacial phenomena, exist along the mainland shore of Lake Michigan and on certain nearby islands in Benzie and Leelanau Counties, Michigan, and that such features ought to be preserved in their natural setting and protected from developments and uses which would destroy the scenic beauty and natural character of the area."

The Congress also directed that

"…the Secretary (of the Interior) shall administer and protect Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore in a manner which provides for recreational opportunities consistent with the maximum protection of the natural environment within the area."

The federal legislation establishing the Sleeping Bear National Lakeshore also requires NPS to avoid negative impacts to private property from any development of the Lakeshore:

"[i]n developing the lakeshore, full recognition shall be given to protecting the private properties for the enjoyment of the owners," and "[i]n developing the lakeshore the Secretary shall provide public use areas in such places and manner as he determines will not diminish the value or enjoyment for the owner or occupant of any improved property located thereon." (16 U.S.C. §§ 460x(b) and 460x-5(d), 1970);

Certainly the proposed Segment 9 will impact private property, especially at the intersection of M-22 and Traverse Lake Road (TLR), and the massive retaining walls to be constructed along east TLR will detract from the enjoyment of a scenic wilderness road through a local neighborhood.

Here is the mission as stated on the back of the NPS Lakeshore business card: “To conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and wildlife therein, and to provide the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

NPS should stick to its mission to protect natural areas, not develop them. Other options have minimal impact in comparison.

Enabling Lakeshore legislation and local impacts

National Park Service Management Policies

One of the most important aspects is whether the proposed Segment 9 Heritage Trail is consistent with the core values and mission of the National Park Service to preserve and protect natural features that have state, national and global significance. The National Park Service adopted in 2006 Management Policies to govern the various National Parks, including Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore. Here are some key excerpts:

“The most important statutory directive for the National Park Service is provided by interrelated provisions of the NPS Organic Act of 1916 and the NPS General Authorities Act of 1970, including amendments to the latter law enacted in 1978. The key management-related provision of the Organic Act is as follows: [The National Park Service] shall promote and regulate the use of the Federal areas known as national parks, monuments, and reservations hereinafter specified… by such means and measures as conform to the fundamental purpose of the said parks, monuments, and reservations, which purpose is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations. (16 USC 1)” (page 20)

“The fundamental purpose of the national park system, established by the Organic Act and reaffirmed by the General Authorities Act, as amended, begins with a mandate to conserve park resources and values. This mandate is independent of the separate prohibition on impairment and applies all the time with respect to all park resources and values, even when there is no risk that any park resources or values may be impaired. NPS managers must always seek ways to avoid, or to minimize to the greatest extent practicable, adverse impacts on park resources and values.” (Page 20)

“Before approving a proposed action that could lead to an impairment of park resources and values, an NPS decisionmaker must consider the impacts of the proposed action and determine, in writing, that the activity will not lead to an impairment of park resources and values. If there would be an impairment, the action must not be approved.” (page 22)

“In making a determination of whether there would be an impairment, an NPS decision-maker must use his or her professional judgment. This means that the decision maker must consider any environmental assessments or environmental impact statements required by the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA); consultations required under section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), relevant scientific and scholarly studies; advice or insights offered by subject matter experts and others who have relevant knowledge or experience; and the results of civic engagement and public involvement activities relating to the decision. The same application of professional judgment applies when reaching conclusions about “unacceptable impacts.” (page 22)

“Given the scope of its responsibility for the resources and values entrusted to its care, the Service has an obligation to demonstrate and work with others to promote leadership in environmental stewardship. The Park Service must set an example not only for visitors, other governmental agencies, the private sector, and the public at large, but also for a worldwide audience. Touching so many lives, the Service’s management of the parks presents a unique opportunity to awaken the potential of each individual to play a proactive role in protecting the environment.” (Page 24)

Is removing 7,300 trees for a 4 mile trail, building retaining walls 25’ in height through State protected Critical Dune Area, and paving an asphalt path through globally rare and State Concern wooded dune and swale complexes a proactive demonstration of national leadership in protecting the environment?

National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) requirements

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) was signed into law in 1970 to promote efforts that prevent or eliminate damage to the environment. Its purpose was to enrich the understanding of the ecological systems and natural resources and to promote efforts that will prevent or eliminate damage to the environment and biosphere. NEPA requires federal agencies, including the National Park Service (NPS), to assess the environmental effects of their proposed actions before making any decisions and consider any reasonable alternatives. Here are the federal legal requirements which also apply to the decision-making process of Segment 9 Heritage Trail:

NEPA requires federal agencies to analyze the foreseeable environmental impacts, including direct, indirect, and cumulative impacts, of "major federal actions." 42 U.S.C. § 4332(c)(I); 40 C.F.R. § 1508.7.

NEPA requires the analysis and consideration of cumulative effects that result from the incremental impact of the action when added to other past, present, and reasonably foreseeable future actions. 40 C.F.R. § 1508.25(a).

Pursuant to NEPA's regulations, an Environmental Assessment (EA) must "provide sufficient evidence and analysis for determining whether" a project will have a significant impact on the environment. 40 C.F.R. § 1508.9(a)(1).

NEPA requires an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for any major federal action that may significantly affect the quality of the human environment. 42 U.S.C. § 4332(2); 40 C.F.R. § 1502.3.

NEPA requires an agency to "study, develop, and describe appropriate alternatives to recommended courses of action in any proposal which involves unresolved conflicts concerning alternative uses of available resources." 42 U.S.C. § 102(2)(E). Agencies "shall rigorously explore and objectively evaluate all reasonable alternatives, and for alternatives which were eliminated from detailed study, briefly discuss the reasons for their having been eliminated." 40 C.F.R. § 1502.14(a). 66. This "alternatives provision” applies even when the agency prepares an environmental assessment, and it requires the agency to give meaningful consideration to reasonable alternatives. See 40 C.F.R. § 1508.9(b). "The obligation to consider alternatives to the proposed action is at the heart of the NEPA process, and is operative even if the agency finds no significant environmental impact." Dine Citizens Against Ruining Our Environment v Klein, 747 F.Supp.2d 1234, 1254 (D. Colo. 2004) (citing Greater Yellowstone Coal v Flowers, 359 F.3d 1257, 1277 (10th Cir. 2004).

NEPA requires agencies to use high quality information and accurate scientific analysis; disclose "any responsible opposing view;" "make explicit reference …to the scientific and other sources relied upon for conclusions in the statement; disclose any scientific uncertainties; and complete independent research and gather information if no adequate information exists (unless the costs are exorbitant or the means of obtaining the information are not known)." 40 C.F.R. §§ 1500.1(b), 1502.9(b), 1502.22, and 1502.24.

To determine whether a proposed project will have a "significant" impact on the environment (requiring preparation of an EIS), NEPA requires an agency must evaluate, among other things, "unique characteristics of the geographic area" and "the degree to which the effects on the quality of the human environment are likely to be highly controversial.” 40 C.F.R. §§ 1508.27(b)(3) and (b)(4).

NEPA requires an EA to be revisited if there are significant new circumstances or information relevant to the environmental concerns or alternatives that have bearing on the proposed action or its impacts.

NEPA “ensures that the agency. . .will have available, and will carefully consider, detailed information concerning significant environmental impacts; it also guarantees that the relevant information will be made available to the larger [public] audience.” Robertson v Methow Valley Citizens Council, 490 U.S. 332, 349; 109 S.Ct 1935; 104 L.Ed.2d 351 (1989).

Environmental Assessment (EA) and Environmental Impact Statement (EIS)

An Environmental Assessment (EA) serves as a review document that evaluates the potential environmental impacts of a proposed federal action. An EA considers the purpose and need of the proposal, alternatives to the proposed action, and a review of the impacted human environment. If none of the potential impacts assessed in the EA are determined to be significant, then a Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI) is prepared.

The primary purpose of an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) is a more rigorous analysis, as mandated by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), to ensure that agencies consider the environmental impacts of their actions during decision-making processes. An EIS provides a comprehensive consideration of significant environmental impacts and presents reasonable alternatives that can either avoid or minimize adverse effects or enhance the quality of the environment. An EIS must be supported by evidence that the necessary environmental analyses have been conducted; the methodology should ensure scientific accuracy. According to the Environmental Protection Agency an EIS contains:

Purpose and need statement: Explains the reason the agency is proposing the action and what the agency expects to achieve.

Alternatives: Consideration of a reasonable range of alternatives that can accomplish the purpose and need of the proposed action.

Affected environment: Describes the environment of the area to be affected by the alternatives under consideration.

Environmental consequences: A discussion of the environmental effects and their significance.

Submitted alternatives, information, and analyses: A summary that identifies all alternatives, information, and analyses submitted by state, tribal, and local governments and other public commenters for consideration during the scoping process or in developing the final EIS.

2009 Leelanau Scenic Route Trailway Plan & Environmental Assessment

After a workgroup consisting of various community representatives completed their identification of a trailway plan, the National Park Service (NPS) published a 2008 Leelanau Scenic Route Trailway Plan and Environmental Assessment along with a public comment period in October 2008. The proposed route included an on-road trail along Traverse Lake Road. The Heritage Trail plan was revised and NPS then published the 2009 Leelanau Scenic Route Trailway Plan and Environmental Assessment along with a second public comment period in March 2009. Not even one single comment was received, either in support or with concern; one wonders about the extent of pubic notification during the winter. The proposed route included an off-road trail along Traverse Lake Road. NPS then issued a “Finding of No Significant Impact” (FONSI) in August 2009. NPS relied on the March 2009 Environmental Assessment (EA) in determining “no significant impact” and did not complete an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) as required by NEPA. No documentation is available on scientific determinations that were conducted to verify the impacts. The only documentation on potential impacts is contained within the 2009 Trailway Plan and Environmental Assessment.

The Trailway Plan and Environmental Assessment (EA) is the basis for the public to understand what is being proposed, the trail route and the impacts. The information must be accurate and complete in its assessment of the proposed trailway plan. Each segment must be evaluated separately and the assessment to analyze the impact based on the unique features specific to that segment. One cannot simply take an assessment from another segment and infer that it is the same for a different segment.

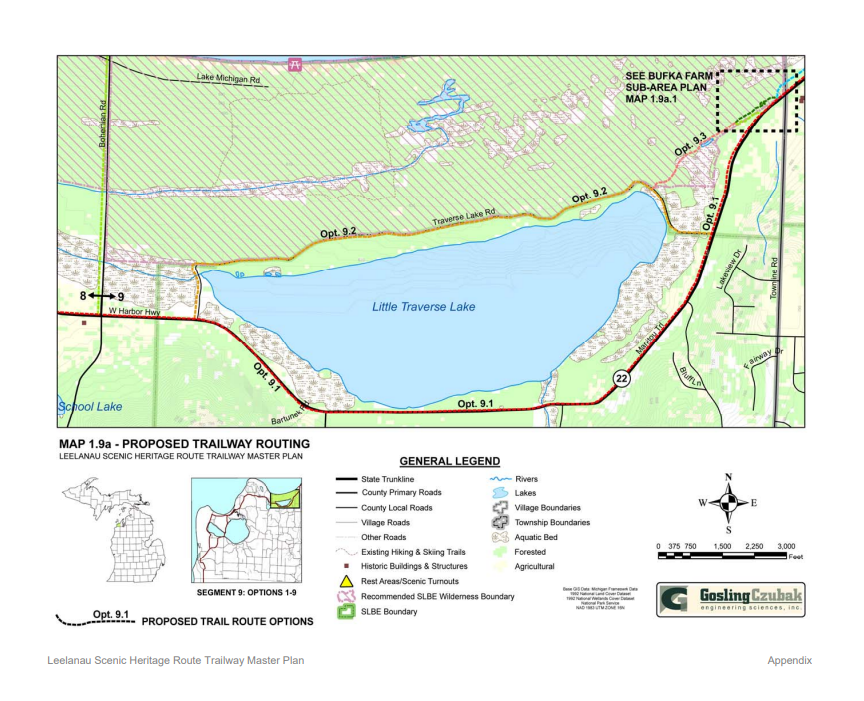

For Segment 9, the only route options considered were Option A following M-22 around the south side of Little Traverse Lake or Option B following Traverse Lake Road (TLR) along the north side. NPS did not look at other options in the Good Harbor area, and did not give an explanation of why other alternatives were not considered in the overall route determination in this Good Harbor area.

There are a few important pieces of information that are specific to Segment 9 evaluation in the NPS 2009 Trailway Plan and Environmental Assessment:

Proposed route maps Segment 9 - Map 1.9a and Map 1.9b, Appendix, page 40-41

Some key route segments are Opt. 9.1 - segment along M-22, Opt. 9.2 - segment along TLR, Opt. 9.3 - segment from TLR to Bufka Farm, Opt. 9.3-9.6 segments around Bufka Farm, Opt. 9.7 segment from Bufka Farm to Good Harbor Trail / CR 651.

Segment 9 Impact to the Environment - Table 17, Appendix, page 30

The criteria for evaluation of impact to the environment included: Topography, wetlands, streams & creeks, soils, wildlife, vegetation, land use, and cultural resource.

Segment 9 Impact to Feasibility - Table 18, Appendix, page 30

The criteria for evaluation of impact to feasibility included: Recreational Experience, SLBE visitor experience, safety, cost, and operations & maintenance.

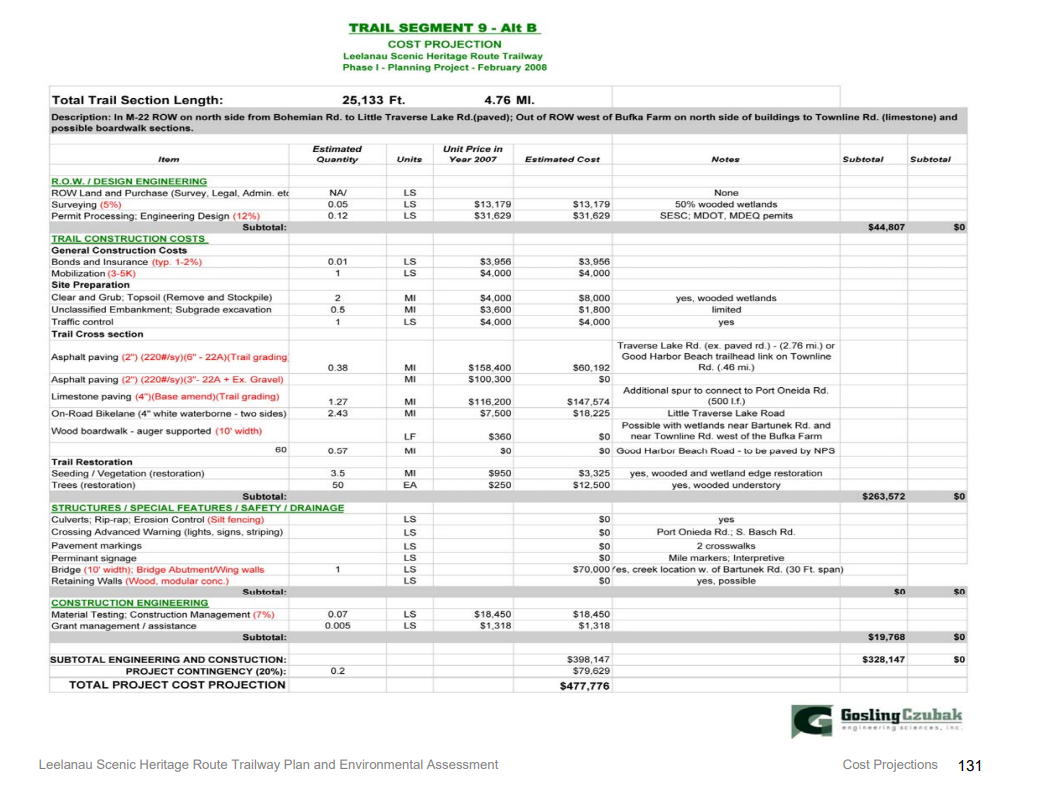

Trail Segment 9 Cost Projection - Chapter 5, page 131

A cost projection is prepared for each segment to reflect the identified design elements that are required for trail construction of the proposed route.

VIEW A COPY OF ALL THE DOCUMENTS HERE

Another troubling aspect of NPS's decision to issue the FONSI is the fact that it did so before final decisions were made relating to the trail's route and related construction means and methods. The trail route was imprecisely drawn on a map and was not surveyed until 2023. Even fifteen years later, some of the design elements were not known, including the extent of excavation and design requirements for routing the trail through steep and large State-protected Critical Dune Area. According to the botanist who completed the botanical survey, “The field survey found Section 4 was found to be entirely within the wooded dune and swale complex natural community and the trail follows dune swales in part, even though the map for Segment 9 shows that the trail is outside of these sensitive ecosystems.” The final route was not determined in 2009, even as a 2018 workgroup was formed to work through design and route options. So it was premature to issue a FONSI for Segment 9.

Environmental Assessment for Segment 9 flawed with omissions

Topography: NPS assigned an impact score of “0” with notation “existing; negligible slope.” The Borealis botanical survey identified steep and large State-protected Critical Dune Area along TLR. Mansfield & Associates in their recent engineering analysis demonstrated the need to remove a large portion of the Critical Dune Area and construct 25’ retaining walls for nearly 950’ due to the topography challenges. That should have been identified in the EA and a score of “3” assigned due to the impact to topography along the proposed trail route.

Wetlands: NPS assigned an impact score of “0” with no notation of any wetlands or boardwalks. The Borealis botanical survey identified a long portion of rich conifer wetlands that also has a population of State Special Concern species located within 15’. The wetlands should have been identified in the EA and a score of “3” assigned due to extensive regulated wetlands and required boardwalks.

Streams & Creeks: NPS assigned an impact score of “0” with no notation identifying any streams. The Borealis botanical survey identified the need to cross Shalda Creek with a wide span bridge. This stream crossing should have been identified in the EA and a score of “2” assigned due its size.

Soils: NPS assigned an impact score of “0” with no notation identifying any soil limitations as was done for the other sections in the Segment 9 table. There are extensive wetland soils along TLR, and, for consistency with other scoring, the soils category should have been assigned a “3” for limited muck soil.

Wildlife: NPS consistently assigns a “0” to wildlife in the EA when trail traffic does interrupt wildlife patterns and elevated boardwalk construction creates a barrier to wildlife. It does not appear that the reviews placed much consideration on wildlife interruption, especially in wilderness areas like south of Bufka Farm. Option 9.2 should be assigned at least a score of “1” for the long elevated boardwalks creating a barrier to the movement of large animals.

Vegetation: NPS consistently assigns a “0” to vegetation impacts. The Borealis botanical survey identified 7,300 trees to be removed along the length of Segment 9, with 3,933 trees along the TLR section. The impact to vegetation should be assigned a score of “2” or “3” based on the magnitude of tree removal, which was unknown in 2009.

Land Use: NPS assigns a score of “2” with the notation of “private land use/Lake Assoc, Co road chip seal.” The trail does cross five private properties along the trail route. The impact to the residence at the intersection of TLR and M-22 should be assigned a “3.”

Cultural resource: NPS assigns a score of “2” with the notation “Trail borders recommended wilderness boundary.” NPS assigns a score of “3” to option 9.3 which borders the same wilderness area and assigns a score of “0” to the other sections, including Opt 9.7 north of Bufka Farm that also borders the same wilderness area without identification of that fact. The reality is that in 2009, Segment 9 did not border the proposed wilderness area; it went right through the preferred alternative for proposed wilderness area as identified in the 2008 General Management Plan.

As part of the cultural resource, NPS should also have identified that 85% of the proposed route went through State-protected Critical Dune Area and identified the globally rare and state concern wooded dune and swale complex, which is also habitat for the State- threatened pine drop. Both of these ecosystems were identified in the Borealis botanical survey but were not identified in the NPS 2009 EA. That should have resulted in an assignment of “3” to the scoring, including a discussion of wetlands and other categories.

Viewsheds: NPS assigned a score of “0” with no notation. TLR is a scenic wilderness road with a tree canopy over the road creating a beautiful view experience. The staked route indicates the trail will be close to the road in some portions, requiring the removal of trees for 25’ along this wilderness road. More significantly, Mansfield & Associates identifies the need to build nearly 950’ of retaining walls with height as much as 25’ in height. That design element will drastically change the character of a scenic tree-canopied wilderness road viewshed along TLR. There should have been identification of that change with an assigned impact score of “3”. It is interesting that Cleveland Township has an ordinance protecting the viewshed as the scenic beauty is deemed important to the local community.

NPS Perspective of the Environmental Assessment

Scott Tucker, Superintendent of Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, has publicly stated:

“There were no surprises in the [Borealis botanical] study. Back in 2009, we followed a very prescriptive process for an EA, as outlined by the NEPA. That process was followed to a T … The EA did not say there would be no impacts; it said there would be impacts, but the NPS ultimately found that they were not significant impacts,” March 6, 2024

"the Borealis study “highlighted all the things the EA identified in 2009. There were no surprises in there.” February 17. 2024

While that might be the intent of NPS, it might not be accurate in past practice. The NPS assigned impact scores of “0” to topography, wetlands, streams & creeks, vegetation, and viewsheds for the proposed route along Traverse Lake Road, implying there are no impacts. The NPS 2009 EA did not identify the ecosystems that the Borealis botanical study found. The NPS 2009 EA for Segment 9 has large omissions of significant aspects, environmental features, and design elements, regardless of what impact score should be assigned. The scoring presented to the public does not accurately reflect the reality or impacts in the actual environment. If scored correctly, Segment 9 would have the highest impact of any segment of the Heritage Trail and would push the limits of impact scoring across many categories.

This information is important as it is used to determine if there is a significant impact. A segment scoring the highest impact “3” should result in a conclusion that there is a significant impact. If the information in the environmental assessment is faulty, then the conclusions of the EA would also be faulty. Keep in mind - there was no mention of any scientific basis for determining the impact to the environment and certainly no botanical field study was done or any in-depth engineering analysis completed, both of which are available now through independent analysis. Is the determination of “no significant impact” for Segment 9 a subjective determination?

For many, it is “significant” to build boardwalks through rich conifer wetlands with a known population of State Special Concern Species, to push a new path through wooded dune and swale complexes that are globally rare and of State concern, to route 85% of trail through State- protected Critical Dune Area, to remove 7,300 trees in wooded dune forests, to build 25’ high retaining walls for 950’ through State-protected Critical Dune Area along a scenic wilderness road, and to build the trail within 10’ of private residential structures. If this isn’t “significant”, what would be significant?

Inaccurate cost estimates due to omitted design requirements

The estimated costs for Segment 9 are presented on page 131, Chapter 5, of the NPS 20l9 Trailway Plan. The costs for the 4+ mile Segment 9 was estimated to be $477,776 or approximately $100,000 per mile. Here is why the cost estimate is not accurate due to omitted design requirements:

There is no cost included to build elevated boardwalk across regulated wetlands which account for 20% of the trail length.

There is no cost included for removal of Critical Dune area and construction of large retaining walls along Traverse Lake Road. Those two design features (boardwalk and retaining walls) are not even identified as needed in the cost projection table.

The estimated costs for removal of 7,300 trees along the trail route and site preparation is $9,800. That is not reasonable for a 4+ mile trail.

The cost projections for Option 9.7, the section between Bufka Farm and Good Harbor Trail / Cr 651 is based on a limestone, not an asphalt path as is being designed now.

There is no cost included for a bridge across Shalda Creek (table references Bartunek Rd?).Option 9.2 in Table 17 - Segment 9 impact to the Environment assigns a score of “0” to Streams & Creeks and does not identify Shalda Creek.

The cost for Option 9.2, which is the 2.43 mile section along Traverse Lake Road, is $18,225 for striping. In Table 18, Segment 9 Impact to Feasibility, the assigned cost scored is “0” with a notation of “utilize existing road with no modification.” But the proposed route in the NPS 2009 Trailway Plan was for a 10’ wide asphalt off-road trail that is significantly different than a shared on-road trail when it comes to construction. Is this an off-road trail along TLT or a shared on-road trail?

These design omissions are not little mistakes but huge omissions that makes the presentation of costs to the public for their evaluation of the proposed route grossly inaccurate. The design features required along the proposed Segment 9 route make it the highest cost per mile of any segment of the Heritage Trail, even with using 2009 pricing. The current projected cost is now $14.5 million and climbing as design elements are engineered. This 30x greater cost than projected is not due to inflation over the last fifteen years. Yes, costs have gone up due to inflation. But this difference in costs is predominately due to the errors and omissions in the 2009 NPS Trailway Plan and Environmental Assessment, not just inflation.

Comparison of NPS 2008 Trailway Plan & EA and the NPS 2009 Trailway Plan & EA

NPS proposed in the 2008 Leelanau Scenic Heritage Route Trailway Plan and Environmental Assessment an on-road trail along Traverse Lake Road as part of the proposed Segment 9. NPS revised the route and in the 2009 Leelanau Scenic Heritage Route Trailway Plan and Environmental Assessment proposed an off-road trail along Traverse Lake Road. Both provided maps 1.9a and 1.9b identifying the route by a line on a map. Both included Table 17 Impacts to Environment, Table 18 Impacts to Feasibility, and Segment 9 Cost projections (Appendix 5). Those key documents can be viewed here for the NPS 2008 EA and for the NPS 2009 EA. If one printed out those five pages for each EA and laid them side by side on a table, it becomes quickly clear they both are the same. NPS’s data, notations and scoring are the same for the off-road trail as they are for an on-road trail. But there is a huge difference in design, construction and impact. Either the EA was never updated for an off-road trail or the EA does not reflect the actual environment. Either way, the information for Segment 9 in the NPS 2009 EA, which was presented to the public for their review, understanding and evaluation of impacts, is grossly flawed with errors and omissions.

Conclusions of Mansfield & Associates after review of NPS 2009 Trailway Plan & EA

Mansfield & Associates concluded in their 2012 review:

“After a careful examination of this Plan, specifically as it relates to Segment 9 of Alternative B: the Preferred Alternative, it is the opinion of Mansfield & Associates, Inc. that there are such gross and significant deviations and conflicts between the Narratives, and Cost Projections, and between the Impact Findings and Assessments in the proposed methods and materials to be used to develop the proposed trailway, that no layperson could ever truly define just what is the intent of the Plan. Now after comparing our initial conversations and interpretations, with our reading of Plan [and EA] as it pertains to Segment 9 of Alternate B, and being persons and professionals who work with such terminology, plans and relate exhibits on a daily basis, we cannot say with any certainty what, even in concept, is being proposed in this segment [e.g. on road or off-road trail?]. The final review of this plan simply begs the question [in relation to Segment 9] – “What are they proposing?” (Page 22)

“In reviewing this Plan and without further knowledge of the process under which the Plan was developed, it is our opinion that the discrepancies are so severe that any adoption of this plan should be voided, and the study re-opened and re-heard.” (page 22).

Time for an EA and EIS that accurately evaluates environmental impacts and considers broader alternatives

No Environmental Impact Statement was completed for Segment 9. The data relied upon by NPS in making its FONSI in connection with Segment 9 of the Trail was inadequate and incomplete as presented in the Segment 9 EA, and NPS failed to adequately disclose and analyze the likely effects of the Trail. In issuing the FONSI, NPS relied on the flawed environmental assessment, and thus the finding of “no significant impact” would also be flawed. Neither the EA nor the FONSI reference any studies or data used to support the conclusion that there is no significant impact to the human and natural environments, including studies or data related to human and traffic impacts that Segment 9 of the preferred Alternative B route will have upon the residents of Traverse Lake Road and private property, destruction and dissection of wildlife habitat, impact on wetland areas, or excavation of critical dune areas. The EA also did not consider all alternatives available in the Good Harbor area as required by NEPA and did not fully evaluate their feasibility in minimizing environmental impacts in comparison to Option B of Segment 9.

Mansfield & Associates independently completed in 2012 “Review of the Scenic Heritage Route Trailway Plan and Environmental Assessment” that was commissioned by Little Traverse Lake Association. Mansfield & Associates evaluated the NPS 2009 EPA and compared it to actual field observations on the ground as the route was analyzed. While the route was not staked until 2023, Mansfield & Associates did walk the route based on a map, took field notes, and then analyzed the information presented in the NPS 2009 Environmental Assessment. Access to the full Mansfield review has been provided. The report has a wealth of insights that are still valid and have been subsequently verified by the Borealis botanical study. Here is part of their findings:

“Because of the inconsistencies found in the plan, it is virtually impossible for the layperson to analyze the Impacts to the Environment. Should the narrative be correct, the Impacts to the Environment would combine to make this segment one of, if not the highest, scoring segments along the entire route.” (page 20)

Inaccurate assessments of environmental impacts due to omissions in identifying ecosystems

To fully understand the inaccuracies in the NPS 2009 EA, one must look more closely at Table 17 that details the specific information used in determining the environmental impacts. Mansfield & Associates provides a greater analysis in their EA review for all of Segment 9 but will limit the following discussion below to just Option 9.2 in Table 17, the trail section along Traverse Lake Road (TLR):

Public feedback not well received

NPS and TART Trails reference the many meetings that went into the planning process of the Heritage Trail. There was a lot a work and community effort that went into the original concept of the overall trail idea. However, since the Heritage Trail was proposed in 2008-2009 Trailway Plans, very little opportunity has existed for the public to engage in a meaningful way, especially when it comes to specifics of the design for Segment 9 or a bigger discussion of the alternatives. While conversations take place, it often feels like concerns are not heard or taken into consideration. It’s as if 2009 is frozen in time despite times changing the last fifteen years with many more people finally gaining awareness as to what is being proposed as more scientific and engineering information becomes publicly available.

2008 & 2009 public comment opportunities

NPS held a pubic comment period in October 2008 after publishing the first Leelanau Scenic Heritage Route Trailway Plan and Environmental Assessment. Over 70% of all public comments raised concerns about routing the trail in the Little Traverse Lake area, whether on-road or not. The 54 comments received highlighted the unique environmental features and the potential impacts. The trail was moved from a shared on-road trail to an off-road trail in the revised 2009 Trailway Plan and Environmental Assessment. Not one single public comment was received in March 2009, either in support or raising concerns. Many have questioned the extent of public notification in the winter, whether people felt like they had already submitted comments in October and did not realize they needed to resubmit, or felt like their concerns over the environment where ignored with moving the trail off-road despite their already expressed concerns.

The awareness and available information has grown since 2009, at which time the trail concept was not on everyone’s radar. Trail construction starting in 2012 increased interest, awareness and scrutiny. Many groups engaged in conversation about concerns, but it was like everything was frozen in time in 2009, despite new information coming forth.

Local community feedback

Little Traverse Lake Association, along with many others including Sleeping Bear Naturally, began to evaluate the proposed Segment 9 route in more depth, brought awareness to the environmental concerns, and proposed alternative solutions. NPS and TART Trails did not want to hear those efforts since the trail route was established in 2009; they shut down any conversation about a bigger perspective of routing trail in the Good Harbor region. The concerns were simply labeled as extreme by a “minority” of “NIMBYs” (Not In My Back Yard). Using NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard) seems to be a way to label and marginalize people by name-calling; perhaps one is not really open to hear what others may have to say. In fact, everyone should be listening to what the local community says because they know the environment and ecosystem better than anyone else, even perhaps a person in a room drawing a line on the map. They walk it, live it and appreciate it daily in ways visitors rarely appreciate or experience. It’s only natural that they are the first ones to sound the alarm when the environment is threatened.

In a July 4, 2024 Traverse City Record Eagle story, the Director of Development for TART Trails publicly stated: “TART Trails has intentionally decided not to engage with a small but vocal group of homeowners on Little Traverse Lake who have been outspoken in dissent of the pathway to Good Harbor, known as Segment 9, of the Sleeping Bear Heritage Trail.” First, TART Trails should be working with local communities, not bulldozing over their concerns and refusing to work with the local community. Second, it is not a small group of homeowners. A survey of 150 local residents who own property around Little Traverse Lake was completed in July 2024. 84% oppose or strongly oppose the proposed Segment 9 Heritage Trail. 80% are greatly concerned about impacts to ecosystems and 85% are greatly concerned about building large retaining walls through Critical Dune Areas. Area residents also do not think Segment 9 is really needed and believe that better alternatives exist. Just 11% support or strongly support the existing plan. A copy of the survey results can be found here.

Little Traverse Lake Association (LTLA) has diligently been asking for an accurate Environmental Assessment because they are intimately aware of the unique ecosystems that exist along the proposed Segment 9. LTLA is an active environmental organization passionate about protecting the lake, watershed, and environment they live in. They hired an expert botanist to do a botanical survey so there was a scientific identification and analysis of the ecosystems and environmental features along the proposed Segment 9. NPS should have done that but didn’t. Congratulations to LTLA for doing what should have been done in 2009 by NPS, who never did any environmental analysis during the last fifteen years. However, some do not want to listen to real scientific findings and wrongly dismiss concerns of a local community out of hand. Furthermore, LTLA has not been against the Heritage Trail but has actively suggested viable alternatives to create recreational opportunities.

Cleveland Township unanimously passed resolutions expressing concern about the impacts of the proposed Segment 9 and endorsing routing the trail in the recreational zone along Bohemian Road / CR 669 and Lake Michigan Road, fully supporting LTLA in their efforts.

2018 NPS Trail Workgroup

NPS revisited specifics of the design of the proposed Segment 9 route by establishing in 2018 a Segment 9 workgroup to relook at the proposed routing, which included another public comment opportunity. The workgroup members were not allowed by NPS to discuss, analyze, or suggest other alternatives for creating recreational opportunities within the Good Harbor region. Even in the 2018 NPS trail workgroup effort, the route was not staked, no botanical survey was done, and engineering designs were not explored in depth, certainly not for the critical dunes along east Traverse Lake Road.

During the 2018/2019 public comment period, users could post comments via an interactive trail map. Over 90% of the 230 posted comments (click here for a copy of comments) raised concerns about the proposed trail routing or suggested alternative routing, but that did not alter the proposed Segment 9. Nothing changed. Many felt like it was only an exercise for NPS and TART Trails to say they had a public comment period while the voices were not really heard or were simply ignored by focusing only on positive trail comments. “Some are for it, some against it” doesn’t create validity for the planning process by dismissing key public input.

Questions to consider

Why does local community input not play a greater role in the process of planning recreational trails? Do NPS and TART Trails have accountability to listen to residents and the local community? When will a broader public discussion be allowed to take place about the best way to create recreational opportunities in the Good Harbor region? Why have the environmental aspects in this Good Harbor area been given the back seat to paving asphalt trails as the number one priority? Why can’t Segment 9 be evaluated independently from the existing 22 miles of the Heritage Trail?

2009 is not frozen in time. Fifteen years have gone by. More is known scientifically, environmentally, and engineering-wise. The route was finally staked in 2023 for all to see and understand. The public has a greater understanding of concerns and alternatives than ever before with access to important information. Plans can change, even now. It is never too late when it makes sense to reevaluate. If one started planning recreational opportunities for the Good Harbor area with all the information available today, the proposed plan would not be the same. One doesn’t keep blindly moving forward building a house when the blueprints are flawed.

Background on Legal Lawsuit

Many are aware of the lawsuit that was filed by Little Traverse Lake Association regarding the proposed Segment 9 Heritage Trail, but few understand the ruling. The court did not make a determination about whether NPS correctly conducted a valid environmental assessment or if all the NEPA requirements were met leading up to the finding of no significant impact. The case never progressed to the opportunity to argue those points for the judge to evaluate. The judge ruled on a technicality related to standing. To gain a better public understanding, here is the background information provided in an LTLA document that is on the LTLA website along with a copy of the complaint:

LTLPOA Historical Efforts LTLPOA’s historical position has been to (1) be supportive of trail opportunities, (2) raise awareness of concerns related to proposed trail construction, and (3) present alternative win-win opportunities. There have been numerous presentations and communications with various stakeholders over the years, including submitting public comments (initially in 2007 and during the 2018 public comment period) and various petitions that included 70% of TLR residents.

Understanding Lawsuit Scope and Ruling After exhausting all remedies to communicate concerns, a federal lawsuit was filed and specifically made these two requests as a course of action: (1) complete an accurate and in-depth Environmental Assessment for the proposed Segment 9 off-road trail, and (2) consider all alternatives and compare impacts. Both are required under the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA), including for phased project segments.

The court never fully evaluated or made a ruling on whether an accurate environmental assessment was completed, whether all alternatives were exhausted, or whether one was superior to others. Instead, the District Court ruled that plaintiffs did not have sufficient standing since no public comments were received (either pro or con) during the winter 2008 public comment period, even though plaintiffs did submit comments during the fall 2007 public comment period. The lower court ruling on standing was upheld by the appellate court. Thus, the matter of an accurate environmental assessment or alternatives was never decided by the courts due to the technicality of WHEN public comments were submitted to the NPS (2007 public comments did express concerns over environmental impacts of a trail along TLR).

Much has happened since 2016. NPS had another look at Segment 9 in 2018 along with another public comment opportunity. There is also much more information available now as discussed above, including greater understanding of environmental features, engineering designs, and alternatives. NEPA requirements still provide governance, including the requirement to update an EA if there are significant new circumstances or information relevant to the environmental concerns or alternatives that have a bearing on the proposed action or its impacts. Changing circumstances, new information, and NEPA requirements legally supersede whether comments were submitted in 2009 or not.